Living in the Time of Dying – a film

17 September 2020 | Mindfulness

In my own little patch, I am living in a split reality. Personally, I am having a good time – protected from the most difficult impacts of COVID, and enjoying my work, and my life on an island in Queensland. Being white and middle class helps.

But many moments of each day, I feel a shock as I let in the reality of the precariousness of every aspect of this life I am living – because of the climate and ecological collapse that is here already for many creatures including humans, with more to come. Plummeting insect populations are threatening bird life and agriculture across the world. Rises in temperature will prevent plants growing across much of the world this century. Water poverty will be the new normal. I re-read “Collapse” by Jared Diamond. Many other civilizations have arisen and then ended. In about 5 billion years the earth will burn up as the sun expands. This is the nature of things – impermanence. Impermanence is fine, just not now please. At night I wake and think about food and water security – not only for those “others” “over there” in other places, but for “me” and “mine” here in Australia. And you might ask – is this catastrophizing? Is this being a “doomer”? Is this being pessimistic? Carl Jung once said: “The foundation of all mental illness is the unwillingness to experience legitimate suffering.” Is this legitimate suffering?

I find myself oscillating. I give money, and sign petitions and will re-engage with XR when I return to Sydney in a couple of months, but meanwhile I enjoy what I am living and the preciousness of now, and this involves a kind of healthy compartmentalising. But it is maybe the kind of compartmentalising that Greta Thunberg is urging us to give up. Catastrophic impacts will be felt by all of us, everywhere, and human existence as we know it is already seriously threatened. (If you haven’t, do read the science. “The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption” is a good place to start.) Greta asks us to know that the house is on fire and to behave as if the house is on fire.

This is hard for us humans and there are some good reasons why we avoid really “taking in” and acting on the ecological threat:

- Human threat reactivity is set up to avoid immediate dangers not slower, unfolding, emerging ones – which have been arriving over many generations.

- Loss aversion means we’re more afraid of losing what we want in the short-term, than surmounting obstacles in the distance.

- Our built-in “optimism bias” irrationally projects sunny days ahead in spite of evidence to the contrary.

- Business as usual. All of the info we are getting from our institutions advises “business as usual”. And we have our own “business as usual” – having to earn a living, look after children or ageing parents, finding a partner, having kids of our own, seeking education, finding a place to live, paying the rent.

- Humans don’t like uncertainty and our brains respond most decisively to those things we know for certain.

And we don’t like emotions. To be anxious or grief-stricken or angry or despairing about the ecological collapse that is happening is natural, but it is a bit uncool, still. But asking myself to be more optimistic about the future is a weak response I think – intellectually, emotionally and in terms of how to live with this. How do we want to live? What can we do? Optimism and pessimism are not the point. Everything is impermanent, but are we prepared to look and see clearly and act – not only out of a “I, me, mine” perspective, but to meet the love and grace and grief that arises when a dearly beloved is perhaps gravely ill. The earth is gravely ill.

While Western colonialist culture believes in ‘rights,’ Indigenous cultures teach of

‘obligations’ that we are born into: obligations to those who came before, to those who

come after, and to the Earth itself. When I orient myself around the question ‘what are my

obligations,’ the deeper question immediately arises: ‘From this moment on, knowing what

is happening to the planet, to what do I devote my life?’

Dahr Jamail

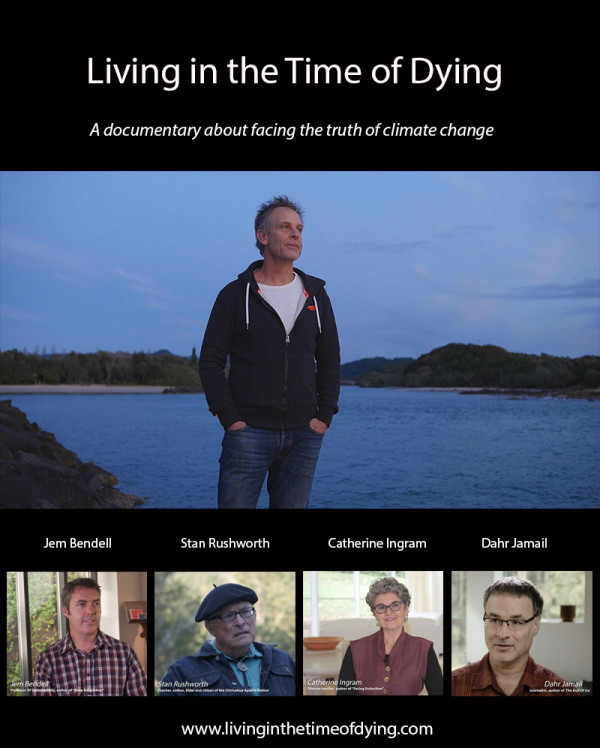

With tenderness and curiosity my colleague and friend Michael Shaw (a passionate anti-bullying educator, mindfulness teacher, spiritual adventurer and now filmmaker) has asked this question, and has made a brave and gentle film called Living in the Time of Dying.

I encourage you to watch it, and see how it moves you.

Listen to Stan Rushworth (Cherokee by birth, elder, teacher, author and Citizen of the Chiruhua Apache Nation) when he tells us that Indigenous people have already been through this threat to everything they hold precious; they know how it feels. Read “The End of Ice” and get on Jem Bendell’s site and read his article "Deep Adaptation". Rilke encourages us: “Let everything happen to you.Beauty and terror.Just keep going.No feeling is final.” The Buddhists would agree.

Be nourished. Feel your feelings. Be a good ancestor.

The Good Ancestor

Every day I walk the hundred years to the hill where my great- great granddaughter sits.

I carry words of blessing and reach to touch her back.

But feeling me near she turns,

sad eyed and heavy with grief

“What was it like?” she asks , ”when the great whales swam

when the birds sang you awake

when the rains came soft

and the soil smelt sweet underfoot?”

And the blessings catch in my throat.

On darker days she turns,

her famished face charred

and eyes, sunk in their bony orbits, burned with curses.

And the blessings froth at my mouth

with the poisonous spume of betrayal.

On the darkest of all days I walk the hundred years

and find no one there.

Let today be the bright day.

Let today be the bright day I lay my hand upon her back

And, feeling me there she turns and blesses me,

saying “Your love was fierce enough, sweet ancestor, your love was fierce enough.”

Daverick Leggett